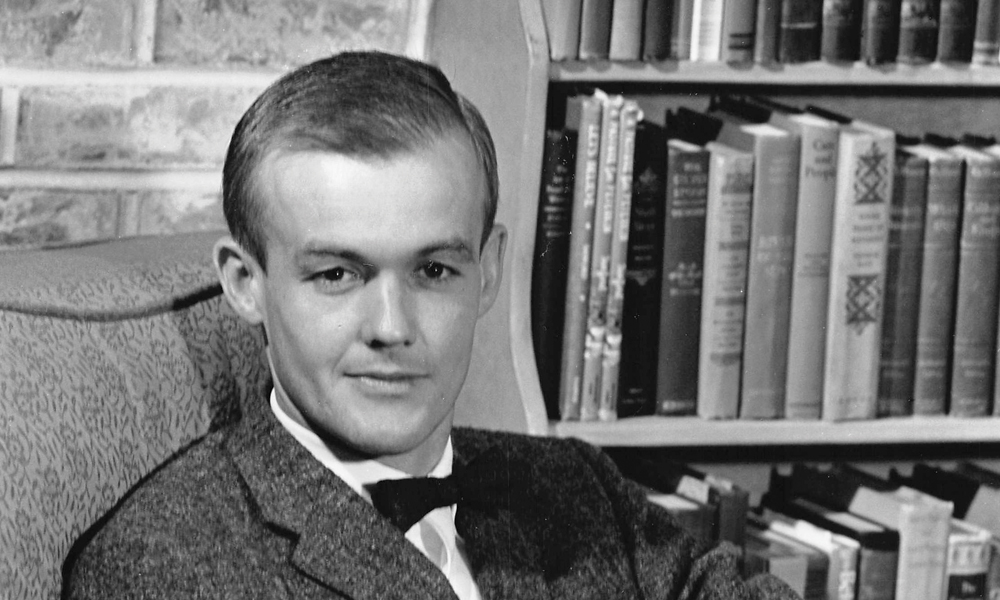

Remembering Ted Sanford

Charles Wright Academy Headmaster 1959-1969

by Tim Sanford ’72

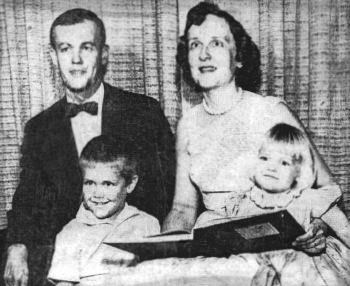

In February 1959 my mom and dad traveled from Connecticut to Tacoma to meet Sam and Nathalie Brown (and others) about the vacant headmaster position at a tiny fledging school in its first year of operation. My dad was 34 years old but looked 24. He had no management or administrative experience. His resume consisted of teaching at a couple of private prep schools on the East Coast. Both Mom and Dad were East Coasters through and through, but Dad was tempted by the interest that Sam and Nathalie had shown in him.

The “campus” of this school was underwhelming: a couple of ramshackle buildings, one a former café, adjoining a dead peach orchard. The school was only grades K-4. On the other hand, the weather was gorgeous, the mountain was out, and they took note that there was nowhere more spectacular than Western Washington on a sunny day. Sam assured them, with a twinkle in his eye, that such weather was not unusual for Tacoma in February. They hit it off immediately with Sam and Nathalie, and everyone they met encouraged them to give their little school a try. And so they did.

I was 5 years old when we moved. My parents bought a house in Lakewood. We lived there for 10 years. I attended Charles Wright from kindergarten through ninth grade; my sister, Wendy, went to kindergarten at CWA in 1961-62 and then (of course) went to Annie Wright. My brother, Lindsay, was born in 1962 and ultimately went to school at CWA for two years before we moved on.

Every day my dad and I drove to school together. We always went by way of Steilacoom because it was prettier. Most of the way to Steilacoom went through farmland, then from Steilacoom we looked out at the Sound and McNeil Island where the convicts lived before driving up the big hill to the school. We had to get there before the rest of the kids did, because Dad wanted to stand in front of the unassuming schoolhouse to greet the kids and their parents as they arrived. Early on, CWA got a school bus, and then several. Dad greeted them, too. Dozens of little boys in white shirts, blue V-neck sweaters, and salt and pepper cords—the Lower School uniform then. Dad stayed at the school after the kids went home to get his work done. I hung out and did my homework until we drove home through the usual drippy gray weather. (It didn’t take my parents long to realize Sam Brown had been pulling their leg about the weather.)

After the Upper School was built, Ray Smith became the head of the Lower School and took over the task of greeting the Lower Schoolers as they arrived in the morning. Ray was perfect for the job: smart, organized, and genial; but, for us Lower School kids, slightly sinister. You did not want to break the rules and suffer Ray’s wrath, as

Geordie Weyerhaeuser ’72 and I discovered when we got into a bit of an altercation and were called into his office. Gulp. That turned out to be a bonding experience for Geordie and me that actually strengthened our friendship.

My dad and I had lots of time to visit on those drives to and from school. My dad did most of the talking, when he felt like talking. I learned a lot about what it meant to be a headmaster. It will not come as news to those who knew him, but he was an intense perfectionist. He had accepted Sam and Nathalie’s vision for Charles Wright, and he was going to implement it no matter what. He knew what needed to be done and could get frustrated on those occasions in which he felt things were not moving along as efficiently as he wanted them to. Patience was never his thing. Luckily, he had my mom to come

home to every night. She was his sounding board, his muse, and his best friend.

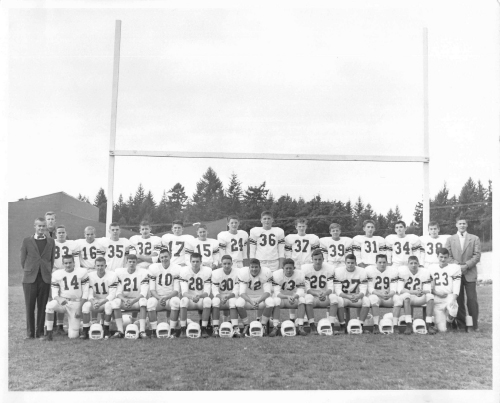

Dad’s perfectionism translated into some real accomplishments for Charles Wright. The school rapidly expanded to include grades K-12; the Upper School was built, along with what then seemed to be a very fancy gymnasium; and the school became accredited and quickly developed an excellent academic reputation. In sum, the fledgling little school became a real school. Dad was always interested in athletics. He played 150-pound football in college (no one over 150 pounds allowed), and he competed in boxing a bit in the Navy. While at Charles Wright, he climbed Mt. Rainier (guided by Lon Whittaker) and went on several backpack trips in the Cascades and Olympics, usually with Charles Wright teachers and/or parents (thank you, Dick Klein, among others). Also, with increasing frequency, he took me on such trips (before I started taking him with me), along with my friends. At one point Dad and I did a multi-day backpack with my classmate Alan Hergert ’72. So naturally Dad established a culture of athletics and outdoorsmanship at Charles Wright.

Some of my favorite memories are from attending sporting events and especially football games. Those of us who were there will never forget beating mighty Orting in a huge upset (13-7 maybe?); or traveling all the way to Raymond on the rooter bus (arriving late with the Tarriers up 7-0; final score: 7-0); or the Vashon game when Assistant Coach Dean Palmer had to be left on the island with the team bus because the last ferry of the night was full. The Tarriers’ success in football certainly was not the result of fancy facilities. Until the gym was built, after-practice showers consisted of being hosed down on the field.

My dad was an excellent artist (and was so tickled by the naming of the CWA art gallery for him), and my mom was an aficionado of the arts herself, appearing in several lead roles with the Lakewood Repertory Theatre. So naturally he made sure the arts were an important part of a Charles Wright education. The most significant step my dad ever took to ensure the success of the arts program at Charles Wright was hiring Donn Laughlin. Indeed, his most important achievement at Charles Wright was probably his retention of an amazing faculty. In the three prep schools, two colleges, and one law school I attended I was blessed with many excellent teachers, but nowhere did I find the across-the-board depth of great teachers that Dad accumulated for Charles Wright. They weren’t just great teachers, but great people, too, and a tight group that seemed to like each other and was committed to the idea of making the emerging school the best around. Dad never thought to micro-manage them in their teaching styles, which varied considerably. Dave Hudson’s meticulous English grammar lessons; Sid Eaton’s free-wheeling, charismatic creative writing class; Tony Mahar’s pugnacious insistence on learning; the beaming face of Jack Cousins. And then there was the wonderful Sam Greeley, I believe my fifth grade teacher. Glasses askew, sweat beading up on his brow, he was totally committed. If he caught you gazing out the window, or whispering to a classmate, you had better be on your toes, as a chalkboard eraser was likely to be hurled in your direction. Duck! This technique would no doubt be frowned upon today, but we did not mind. To the contrary, we appreciated his dedication, and we knew that outside the classroom he was a gentle, sweet man. I could try to list all of the great teachers I remember, but inevitably I would forget someone after all of these years. However, I should mention one more gem that my dad hired, and not just because her son was one of my best childhood friends: Dee Knight, Charles Wright’s legendary first librarian. Dee made every day at Charles Wright a good day.

This was a formative time for Dad, and of course for me. It ended sooner than I would have liked, after my freshman year. But my dad was a restless soul, always looking for new challenges, and so we moved away to another school, this time in California. But not without looking back, often. Mom and Dad ended up retiring to Gig Harbor in 1989.

Thank you, Charles Wright, and thank you to everyone who made it special for us. //